Race, as a concept, aligns with observable genetic population clusters that reflect human evolutionary history. These clusters—typically identified as 5 to 7 major groups (e.g., African, European, East Asian, Native American, Oceanian, and sometimes South Asian and Middle Eastern)—show significant genetic variation within each group but relatively little clinal (gradual) variation between them. This structure arises from historical isolation due to geographic barriers like oceans, deserts, and mountains. Below is the evidence:

1. Genetic Clustering

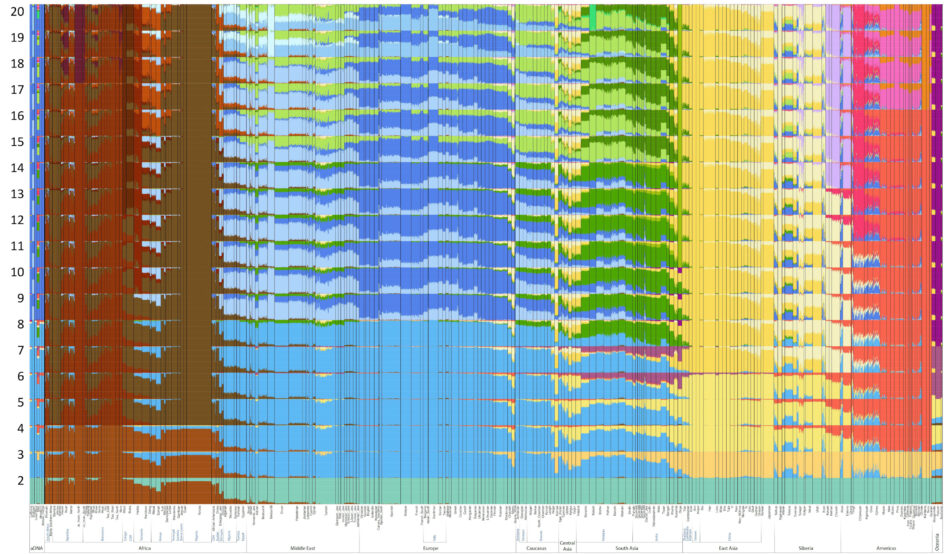

- What it is: Genome-wide studies using tools like STRUCTURE and principal component analysis (PCA) consistently identify 5 to 7 distinct genetic clusters corresponding to major geographic regions.

- Evidence: A landmark 2002 study by Rosenberg et al. analyzed 377 genetic markers across 1,056 individuals and found clear clustering into five groups: sub-Saharan Africans, Europeans/Middle Easterners/South Asians, East Asians, Oceanians, and Native Americans. Later studies with thousands of markers (e.g., Li et al., 2008) confirm this pattern.

- Implication: These clusters aren’t arbitrary—they reflect real differences in allele frequencies shaped by migration, isolation, and adaptation. While clinal variation exists within clusters (e.g., between Northern and Southern Europeans), the boundaries between major clusters are sharper due to historical gene flow barriers.

2. Ancestry Informative Markers (AIMs)

- What it is: Specific genetic markers differ in frequency between populations and can be used to infer ancestry with high accuracy.

- Evidence: Forensic DNA analysis and medical genetics use AIMs to determine an individual’s biogeographic ancestry. For example, certain alleles are far more common in African populations than in European or Asian ones.

- Implication: If race were purely a social construct, ancestry couldn’t be reliably traced genetically. The precision of AIMs shows that population clusters have a biological basis.

3. Phenotypic Differences

- What it is: Observable traits like skin color, facial features, and hair texture vary across populations and are genetically determined.

- Evidence: Skin pigmentation differences (e.g., higher melanin in African populations) are adaptations to environmental factors like UV radiation (Jablonski & Chaplin, 2010). Skeletal morphology and dental patterns also differ systematically between groups.

- Implication: These traits correlate with genetic clusters and reflect evolutionary divergence, not just social perception. Forensic anthropologists can identify race from bones with 85-90% accuracy (Ousley et al., 2009).

4. Disease Susceptibility and Drug Response

- What it is: Genetic variants linked to disease risk or drug metabolism differ between population clusters.

- Evidence: Sickle cell anemia is more common in African populations due to its protective effect against malaria, while cystic fibrosis is more prevalent in Europeans. Pharmacogenomics shows racial differences in drug efficacy (Risch et al., 2002).

- Implication: These patterns wouldn’t exist if genetic differences between clusters were biologically meaningless. They highlight functional differences tied to ancestry.

5. Admixture and Population Structure

- What it is: In regions of recent mixing (e.g., the Americas), genetic ancestry can be traced back to distinct continental populations.

- Evidence: Admixture studies show that individuals of mixed heritage retain genetic signatures from African, European, or Native American clusters, even after generations.

- Implication: This traceability depends on the existence of relatively discrete ancestral clusters, not a smooth global gradient.

Clinal Variation Context

While clinal variation (gradual trait changes across geography) exists within these major clusters—e.g., more diversity within Africa than between Europe and Asia—it doesn’t erase the broader structure. Major genetic discontinuities (e.g., FST ~0.15 between West Africans and Europeans) align with traditional racial categories and are comparable to subspecies distinctions in other animals (Templeton, 2013).

Common Anti-Racist Arguments and Why They’re Scientifically Invalid

Anti-racist arguments often deny the biological basis of race, claiming it’s purely a social construct. While well-intentioned, these arguments frequently misinterpret or ignore genetic evidence. Here’s a breakdown of the most common ones and their flaws, including Lewontin’s Fallacy.

1. Lewontin’s Fallacy

- Argument: In 1972, Richard Lewontin argued that because 85% of genetic variation is within racial groups and only 15% is between them, race lacks biological meaning.

- Why It’s Invalid:

- Statistical Flaw: The 85-15 split applies to single genetic loci, but when multiple loci are analyzed together (e.g., via PCA), population clusters emerge clearly. It’s the correlation of differences across loci that matters, not just the raw percentage (Edwards, 2003).

- Universal Application: This pattern—greater variation within than between—applies to all taxonomic levels in animals (breeds, subspecies, species). For example, dog breeds like Chihuahuas and Great Danes show more variation within the species Canis familiaris than between breeds, yet no one denies breeds are biologically real.

- Biological Significance: Small between-group differences can have big effects. The 15% variation includes genes for observable traits and disease risks, making it taxonomically meaningful.

2. “Race Is Just Skin Deep”

- Argument: Racial differences are superficial and limited to appearance.

- Why It’s Invalid: Genetic differences extend beyond skin to skeletal structure, dental patterns, and physiological traits. Forensic science identifies race from bones, and medical genetics links ancestry to functional outcomes like disease risk. The “skin deep” claim underestimates the depth of population divergence.

3. “No Discrete Boundaries Between Races”

- Argument: Since racial boundaries aren’t absolute, race isn’t biologically real.

- Why It’s Invalid: Biology often lacks sharp edges—e.g., species can interbreed in hybrid zones (like ring species), yet remain distinct. Population genetics uses probabilistic clusters, not rigid lines. The lack of absolute boundaries doesn’t negate the existence of meaningful groups.

4. “Race Is a Social Construct”

- Argument: Race is entirely a human invention with no biological basis.

- Why It’s Invalid: While racial categories are socially defined and often misused, they’re grounded in biological differences. Genetic clusters predate social labels and reflect evolutionary history. Denying this conflates the misuse of race (e.g., racism) with its objective basis.

5. “Human Variation Is Continuous”

- Argument: Genetic variation forms a smooth gradient, not distinct groups.

- Why It’s Invalid: Variation isn’t fully continuous—geographic barriers created discontinuities. For example, the Sahara and Himalayas limited gene flow, leading to clusters with measurable genetic distances (e.g., FST values). Clines exist within clusters, but the broader structure remains.

6. “Race Doesn’t Predict Anything Biologically Meaningful”

- Argument: Racial categories have no practical biological utility.

- Why It’s Invalid: Race correlates with disease risk, drug response, and phenotypic traits. Ignoring these differences risks neglecting real health disparities (e.g., higher hypertension rates in African Americans). This denial can harm science and medicine.

Conclusion

The biological and genetic evidence—genetic clustering, ancestry markers, phenotypic differences, disease patterns, and admixture—supports race as a descriptor of 5 to 7 major human population clusters with minimal clinal variation between them but significant variation within. These clusters reflect evolutionary divergence and aren’t just social inventions. Anti-racist arguments like Lewontin’s Fallacy fail because they misinterpret genetic data and ignore parallels in other species, where similar variation patterns don’t preclude taxonomic distinctions. Acknowledging this doesn’t justify prejudice—it’s simply what the science shows. The challenge is using this knowledge responsibly, not denying it outright.

Leave a Reply